The Unexpected Art of Nostalgia-Based Social Design: What Pokémon Parties Teach Us About Human Connection

Share

There's a fascinating thing that happens when you put a Pikachu headband on a 34-year-old accountant. Something shifts in their posture, their voice, the way they interact with strangers. It's not just costume play or themed entertainment. It's access to a version of themselves they thought they'd outgrown.

This phenomenon sits at the intersection of social psychology, nostalgia marketing, and what researchers call "imaginative play in adults." And it reveals something profound about how we design experiences that actually bring people together in an increasingly fragmented world.

The Neuroscience of Shared Childhood References

When adults encounter symbols from their childhood, something measurable happens in their brains. The anterior temporal cortex lights up, the same region activated during autobiographical memory retrieval. But here's what's interesting: when this happens in a group setting, mirror neurons fire in response to others' nostalgic recognition.

You're not just remembering your own relationship with Pokémon. You're unconsciously responding to everyone else's memories simultaneously.

Dr. Sarah Chen, who studies collective nostalgia at Stanford's Social Psychology Lab, describes this as "temporal social bonding." People don't just share an interest; they share a developmental moment. The eight-year-old who collected holographic Charizard cards exists in the same psychological space as every other eight-year-old who did the same thing, regardless of when or where that happened.

This creates what Chen calls "instant social context." Strangers suddenly have a shared language, shared references, and most importantly, permission to express enthusiasm without social judgment.

The Permission Structure of Adult Play

Here's where it gets psychologically interesting. Adults want to play, but they need social permission to do so without feeling childish or inappropriate. Themed experiences provide that permission structure.

When you label something a "Pokémon party," you're not just choosing a decorative theme. You're creating what sociologist Johan Huizinga called a "play space" where different social rules apply. Inside that space, getting competitive about cartoon trivia isn't weird. It's participating correctly.

This is why some themed parties work while others fall flat. Successful ones understand they're designing permission systems, not just entertainment.

The Complexity of Cross-Generational Engagement

The real challenge isn't getting Pokémon fans excited about Pokémon content. It's creating experiences where a six-year-old discovering Pokémon for the first time can meaningfully interact with someone who's been following it for twenty-five years.

Traditional event planning approaches this wrong. They either aim for the lowest common denominator (which bores experienced participants) or assume shared expertise (which excludes newcomers).

The solution lies in what game designers call "asymmetric cooperation." Different participants contribute different types of knowledge and skills toward shared goals.

Consider how this plays out in practice: A child might have better pattern recognition for visual puzzles while an adult brings strategic thinking to complex challenges. A casual fan contributes fresh perspective while a dedicated follower provides context. Neither is better or worse. They're complementary.

The Social Architecture of Shared Discovery

The most powerful moments at themed gatherings aren't when people display their existing knowledge. They're when people discover something new together.

This is where event design gets sophisticated. You're not just planning activities. You're choreographing small moments of shared surprise and learning.

The "Pokémon or Medicine?" concept works because it creates a level playing field. Nobody's expertise gives them a significant advantage. Everyone is equally confused by whether "Biktarvy" sounds more like a grass-type evolution or an HIV medication. The shared confusion becomes bonding material.

These moments of collective bewilderment serve a crucial social function. They temporarily flatten hierarchies and create what anthropologist Victor Turner called "communitas" - that sense of shared humanity that emerges when normal social structures dissolve.

The Economics of Attention in Social Spaces

Modern social gatherings compete with an unprecedented number of attention alternatives. Everyone at your party has access to infinitely more entertaining content on their phones than you could possibly provide in person.

This creates what economist Herbert Simon called "the paradox of choice in social engagement." Why invest attention in potentially awkward real-world social interaction when you could scroll through perfectly curated digital entertainment?

Successful themed experiences solve this by offering something digital media cannot: collaborative discovery and shared accomplishment.

When people work together to solve puzzles or create something, they experience what psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi called "collaborative flow." This state is inherently social and cannot be replicated through individual digital consumption.

The key is designing activities that require genuine collaboration rather than parallel individual participation.

The Authenticity Paradox in Manufactured Fun

There's an inherent tension in event planning between creating authentic experiences and obviously orchestrating them. People want genuine fun, but they're aware when fun is being engineered for them.

This creates what researchers call "the authenticity paradox of designed experiences." The more obviously planned something is, the less spontaneous it feels. But without planning, experiences often lack the structure necessary for meaningful engagement.

The solution involves what designer John Thackara calls "light architecture." You create frameworks that enable authentic interaction rather than scripting specific outcomes.

In practice, this means designing clear activity structures while leaving room for unexpected directions. You provide conversation prompts but let discussions evolve organically. You set up photo opportunities but don't force people to use them.

Cultural Semiotics and Shared Meaning Systems

Pokémon works as a party theme because it operates as what semiotician Roland Barthes would call a "cultural myth." It's a shared meaning system that transcends its literal content.

When someone references Team Rocket's motto or debates water-type effectiveness, they're not just talking about fictional creatures. They're participating in a cultural language that signals playfulness, nostalgia, and imaginative thinking.

This semiotic richness gives themed experiences depth that purely aesthetic decorations cannot provide. People aren't just surrounded by Pokémon imagery. They're immersed in Pokémon logic, where being the very best is an acceptable life goal and friendship can overcome any challenge.

The Ritual Function of Themed Gatherings

Anthropologist Arnold van Gennep identified three stages of ritual experience: separation from ordinary life, transformation through shared activity, and reintegration with enhanced social bonds.

Themed parties follow this structure precisely. Guests separate from their normal social identities, transform through playful shared activities, and return to regular life with strengthened connections.

The transformation phase is crucial. This is where people access different aspects of their personalities and form new social connections based on those revealed aspects.

Someone who's normally serious gets to be silly. Someone who's usually quiet becomes competitive. Someone who rarely takes creative risks tries something new.

These temporary identity shifts create what sociologist Erving Goffman called "role distance" - the ability to step outside your usual social performance and connect with others from a more authentic place.

The Curation Challenge: Designing for Emergence

The most sophisticated challenge in experience design is creating structures that enable rather than control social emergence.

You want people to surprise themselves and each other, but you need enough structure to prevent awkwardness or exclusion. You want authentic interactions, but you need to provide frameworks that make those interactions possible.

This requires what complexity theorists call "designing for the edge of chaos" - creating enough structure to prevent dissolution while maintaining enough flexibility for creative emergence.

In practical terms, this means having clear activity instructions but flexible timing. It means providing conversation starters but not scripting conversations. It means creating opportunities for different types of people to contribute meaningfully to shared experiences.

The Future of Social Experience Design

As digital interaction increasingly dominates social life, the value of well-designed in-person experiences grows exponentially.

People crave authentic connection, collaborative creation, and shared discovery. But they're out of practice with the social skills these experiences require.

Themed gatherings serve as training grounds for deeper social engagement. They provide low-stakes opportunities to practice vulnerability, collaboration, and creative expression.

The most successful approaches understand they're not just providing entertainment. They're creating temporary communities where people can practice being more fully themselves with others.

Beyond Entertainment: Social Technology

Perhaps the most nuanced insight about themed experiences is that they function as social technology. They're tools for creating specific types of human connection that our culture otherwise struggles to provide.

In a world where most social interaction happens through screens or professional contexts, themed gatherings offer something rare: permission to be enthusiastic, collaborative, and playfully authentic with other people.

The Pokémon theme is just the delivery mechanism. The real product is an environment where adults can rediscover the joy of shared imagination and collective play.

When you design experiences that honor this deeper function, you create something much more valuable than entertainment. You create opportunities for people to remember what it feels like to be genuinely excited about something together.

And in our increasingly isolated culture, that might be the most important service any social experience can provide.

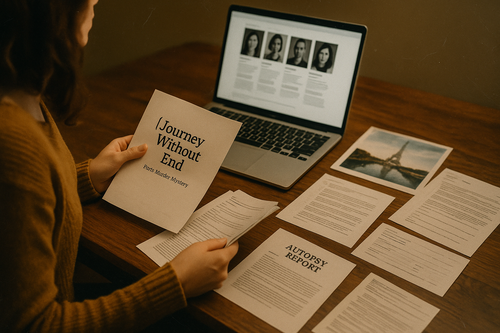

The most successful themed experiences understand they're designing permission systems for authentic human connection, not just entertainment. When people leave talking about the conversations they had rather than just the activities they did, you know you've created something meaningful. Host your own themed party with Min(d)gle Games's editable kits.